Escaping the un-PCs of the 1960s

…Big and slow ‘monocular’ past – nostalgia on steroids

Before we begin, lets disambiguate (in the parlance of Wikimedia). The term PC in our context here is the acronym for personal computer that dates from the 1960s. It’s not to be confused with political correctness which popped up in the 1930s, was reborn with more virulence in the 1980s and 1990s, and is still vexing us today. We’ll leave the latter for a future Rumination.

Yesteryear’s thinking tools

Our brains are miraculous computers, and only now do we worry that they may be supplanted in not only power and speed but also in judgment and control by artificial intelligence (AI). Tools to help us humans do calculations and analysis developed over centuries. Beyond counting on fingers and toes, we could start with the abacus and sundial. But I prefer starting from a more recent point within my own experience.

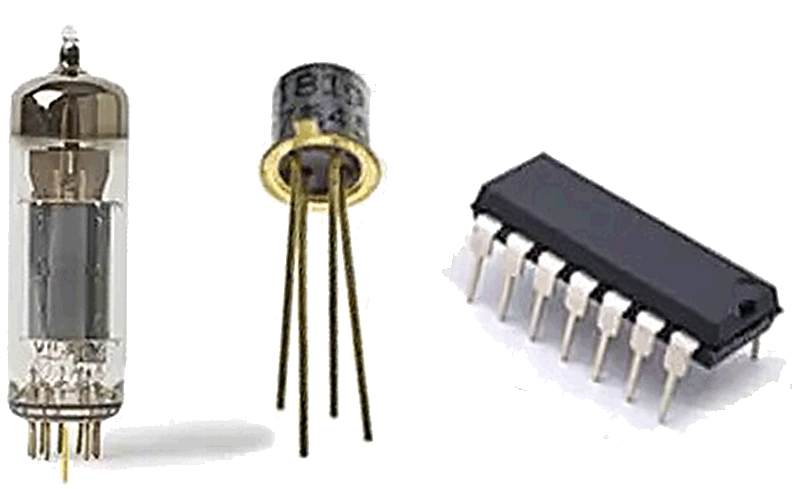

Escaping the vacuum: There was a major leap forward in computing and computers when vacuum tubes, which burned out frequently and at the most inconvenient times, were replaced with the transistor. We still had ‘sources, gates and drains,’ but those names of terminals on a tube now referred to contacts on the new semiconductor device.

That’s when the IBM 709 was succeeded by the IBM 7090 mainframe computer.[1] I cut my proverbial teeth on the tools of that time. Back then, the ancient 1960s analogue to an email attachment was a hand-carried pack of punch cards, rain or shine.[2] Achieving my educational goals depended on submitting my “batch jobs” to a computer center – a center that occupied its own building with human technicians who “ran” my programs, notifying me when the jobs were done.

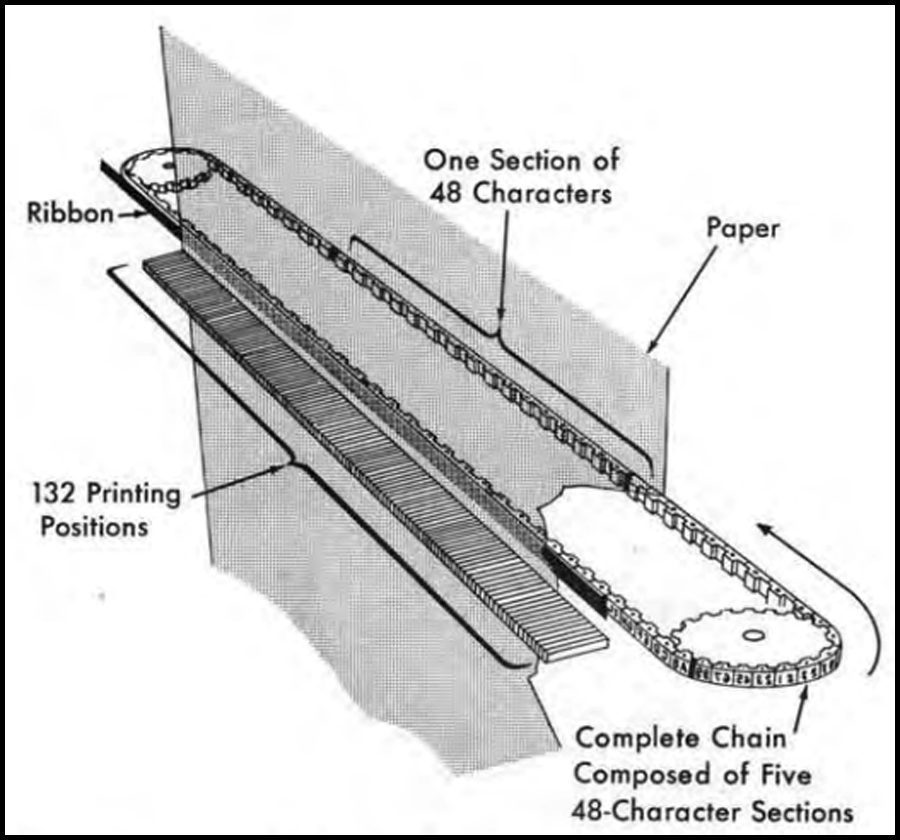

My program’s output was delivered to me as a heavy stack of wide fan-folded lined paper on which was printed every line my coding had prescribed, be they manipulated data, results of calculations from my own formulae, or, my favorite, interposed comments that helped me keep track of where I was within the tree-killing ream. Call me naïve, but back then it seemed miraculous that my painfully produced, usually bug free, lead pencil markings on Fortran coding forms would wind up in my hands as fully analyzed data and evaluated formulae. It was as if that 7090 mainframe monster was speaking directly to me.

From the pass-through portal, a bit like a bank teller’s window, where jobs were handed in, some distance from the big machine, I could hear the printer’s loud clatter as its chain-saw-like character string sought one letter or number after another. In today’s world, those technicians would be required by US OSHA regulations to wear ear plugs to preserve their hearing and sanity.

However, when visiting inside the “machine room”, an occasional privilege granted only by the friendliest technicians who took pity on a lowly grad student, the most impressive sight and sound was not the printer and its character chain, it was the row of tape decks whirring away as the mainframe crunched its numbers. Magnetic tapes are serial beasts. To find specific data, the length of the tape must be searched one bit at a time, at times from beginning to end. Thus, the constant whirring, rewinding, jerky starts and stops as it reads what it has found, then whirring again.

The tape decks in computer centers were later replaced by random access magnetic disc drives that whirred a bit less. Data storage capacities mushroomed, and data retrieval times plummeted.

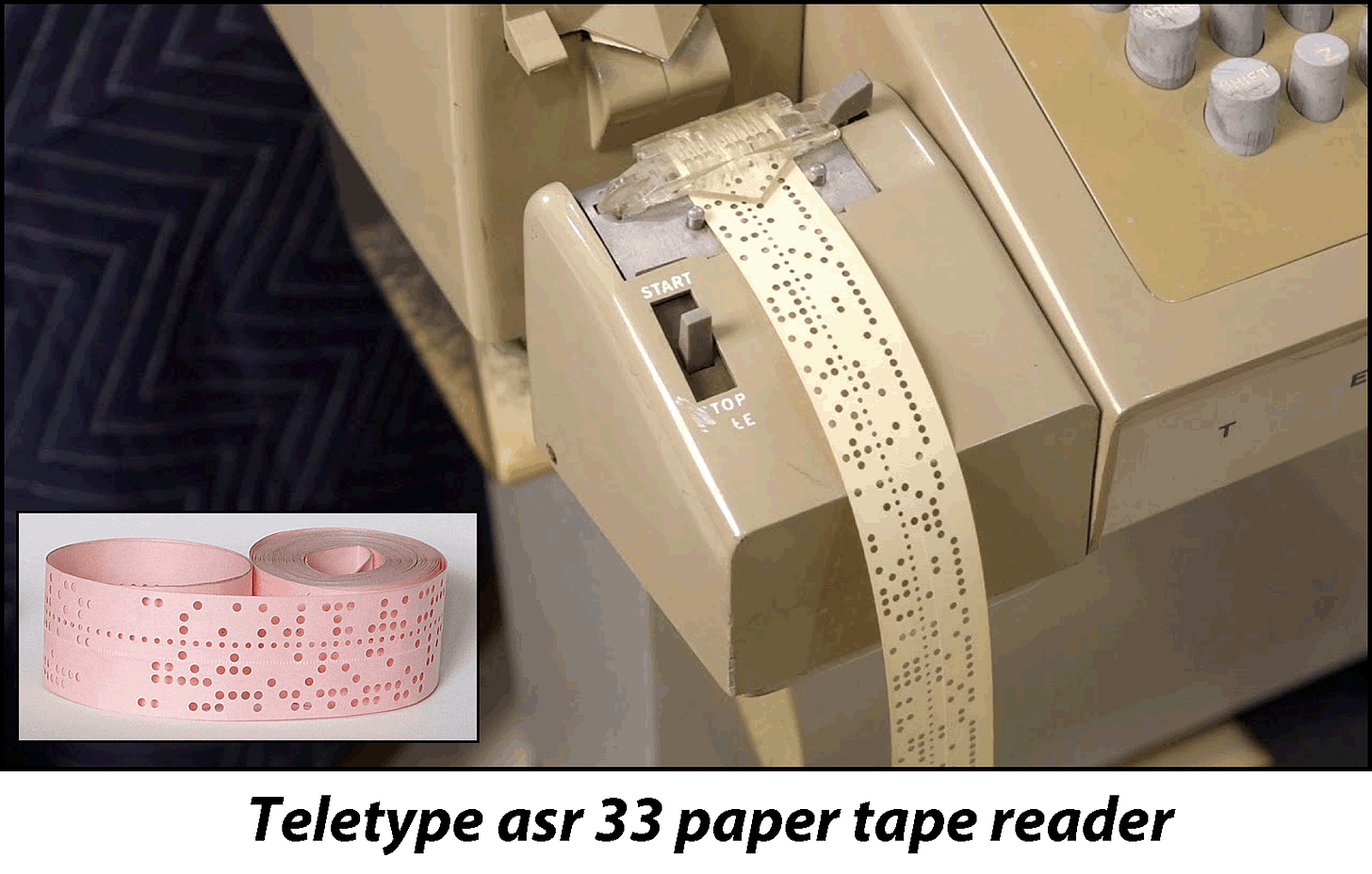

Not only cards got punched: When the intended customer for the output data or instructions was not a human like me, but another machine, and a big tape deck was not available at the receiving end, punched paper tape was used. We could even type our own messages on the Teletype machine and punch our own paper tapes for later use. Just as the Teletypes could print messages incoming via a hard-wired connection to phone lines and fax machines, it could read and print the contents of a paper tape. Handy, if one was careful not to clumsily damage, drop, or deface the tape when feeding it into the Teletype.

Data, a very plural noun

Bits and bytes from very small (kilo) to small (mega) to big (tera) to bigger (peta) to gargantuan (exa):* The floppy discs that were used by our desktop machines shrunk from diameters of 8 to 5¼ to 3½ inches. The magnetic films hosting the data were all physically floppy, thus the name, and were encased in initially flexible sleeves that got progressively stiffer until the 3½ inch version would not bend at all. Some old-timers still call these “diskettes,” a term that to me is reminiscent of some kind of pastry.

Those venerable floppies that could store anywhere from ~300 kilobytes to ~2 megabytes of information were supplanted by compact discs (CDs) and then digital video discs (DVDs) that our PCs burn and read today. These now can store upwards of 10 gigabytes. The newer discs also added a peculiar new phrase to our language that still puzzles me, the “jewel case,” that looks nothing like any jewel with which I am familiar.[3] Local less portable PC storage devices (built-in or stand-alone “hard drives”) now operate in the terabyte range.

The Intel 8086 – still chipping along

Although a great many generations of Intel’s 8086 central processing units (CPUs) on a chip have come and gone, the 8086 is still at the heart of the most modern version’s design. Intel’s x86 architecture underlies even the latest scary Intel Core Ultra chip. Scary, because it sports a new AI capability. An interesting contretemps has arisen over the past few years in that CPUs are seeing competition from GPUs (Graphics Processing Units) that have taken on more than just the graphics chores in our most modern PCs.

Taking it with you

The aphorism, “You can’t take it with you,” from the play and film by the same name [4] did not apply to our need to compute while still on this Earth. Personal mobility was limited by PCs on the desk (desktops) and even on the lap (laptops), although the laptop could be carried in a briefcase. The handheld computer was the holy grail of the time. No sooner imagined then came the PDA (personal digital assistant) in various incarnations like the Palm Pilot and the Blackberry, now in museums, of course.

Superseded by a wide variety of smart phones, with ever increasing features and power, my model Tungsten E2 Palm Pilot still sits by my keyboard, because for some tasks, it’s just easier and simpler to use. The trend from larger cumbersome to smaller convenient was gently reversed when reaching today’s tools – the small smart phone being succeeded by the less small tablet computer, perhaps for folks like me who need larger screens and less squinting. Today, most early and late adopters have both phones and tablets (or “pads”) at their disposal.

Our monocular friend’s descendants have kept up, and if they can do it, so can we. I’d say swapping a club for a phone is a good trade.

What’s next?

Darned if I know! The look back above with its nod to today’s analogues is a lot easier to compose than is a look forward. Someday there will come a physical limit to speed and power and data storage capacity. The digital and cyber worlds will likely find new ways to expand their usefulness for our tasks and trifles and their potential threat to our basic humanity. A light and a dark prospect all in one. Some very smart people who have led the companies at the heart of these developments are opining about both the magnificent and the malign potentialities.[5] The slippery slope approaches rapidly, one that we could not possibly have envisioned from the card-punching days of the 1960s.

___

* The prefixes, mega, tera, peta, and exa, from the Greek mean, respectively, 106, 109, 1012, and 1015, bytes. We wonder when our data devices will byte off a bit more than they can chew.

Credits: Cyclops with club image from https://stock.adobe.com/search?k=cyclops.

Cyclops with phone image from OpenAI.com’s DALL-E image generator.

Intel 8086 chip image from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Intel_8086 .

DVDs image from Adobe Stock #4383696.

Jewel case image from Ref. [3].

Palm Pilot and Blackberry images lifted from eBay.com sales ads.

[1] https://www.historyofinformation.com/detail.php?id=76

[2] See https://www.ibm.com/history/punched-card and sites cited there.

[3] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Optical_disc_packaging

[4] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/You_Can%27t_Take_It_with_You_(play)

[5] E.g., https://time.com/6968820/time100-ai-eric-schmidt-yoshua-bengio/ and https://www.npr.org/2023/05/30/1178943163/ai-risk-extinction-chatgpt

Nota Bene: Others may ruminate differently. But be warned: In my case, seeing or hearing something quite trivial -- a saying, a store clerk’s mannerisms, or bad grammar on a food product’s label – triggers a stream-of-consciousness extrapolation toward grander notions and generalizations. That is what often happens in these posts. ADDENDUM: Those subscribers who have been here for a while will have noticed that at times ruminations have veered into diatribes. I make no apology. I just want my readers to know that it’s quite intentional. When events come close to making the ‘blood boil,’ that discontent bubbles up here.

Disclaimer: Any and all opinions expressed here are my own at the time of writing with no expectation that they will hold beyond my next review of this article. Opinions are like a river, winding hither and yon, encountering obstacles and rapids, and suffering turbulent mixing of silts from its depths and detritus from its banks. But just as a river has its clear headwaters and a fertile delta, so do opinions, notwithstanding any intervening missteps and uncertainties.

Reminder: You can visit the Cycloid Fathom Technical Publishing website at cycloid-fathom.com and the gallery at cycloid-fathom.com/gallery.

Forthcoming posts (unless life intervenes)

Ťħē Ĝřîđş

…in all their incarnations

23 December 2024

I would like to say…

…but to what end?

30 December 2024

Elementary

…Not just a word but a promise

1 January 2025